Immigration from Mexico and Central America

(1848 to Present)

![]() A History of Diversity at Vassar College

A History of Diversity at Vassar College

![]() Eastside College Preparatory School (1976 to Present)

Eastside College Preparatory School (1976 to Present)

The United States has the largest immigrant population in the entire world--four times as many as any other country. Scroll through our U.S. Immigration Timeline to follow the history of immigration legislation in the United States, beginning with the United States Naturalization Law of 1790, which set the first rules for national citizenship.

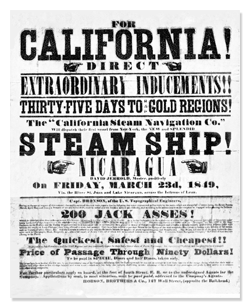

The 19th Century brought the first wave of European immigrants and, in 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo extended U.S. citizenship to Mexican residents of the New Mexico Territory and California. The Gold Rush brought new immigrants from Mexico and Central America as well.

Immigration from Mexico and Central America

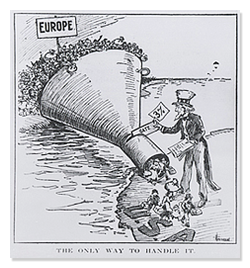

The first large scale migrations from Mexico occurred during the 1910s when over a million Mexican people sought to escape the Mexican Revolution. In 1921, The Emergency Quota Act passed, which restricted immigration into the United States by creating numerical limits on immigration from Europe. No limits were set on immigration from Latin America. The Immigration Act of 1924 restricted immigration from most of the globe, but people still moved quite freely from Mexico, the Caribbean, and parts of Central and South America.

The first large scale migrations from Mexico occurred during the 1910s when over a million Mexican people sought to escape the Mexican Revolution. In 1921, The Emergency Quota Act passed, which restricted immigration into the United States by creating numerical limits on immigration from Europe. No limits were set on immigration from Latin America. The Immigration Act of 1924 restricted immigration from most of the globe, but people still moved quite freely from Mexico, the Caribbean, and parts of Central and South America.

In 1942, over two million Mexican nationals participated in the Bracero Program, allowing Mexican laborers to work in the U.S. under short term contracts in exchange for stricter border. By 1954, Operation Wetback was implemented, utilizing special tactics to combat illegal border crossing, resulting in over a million undocumented Mexicans being deported.

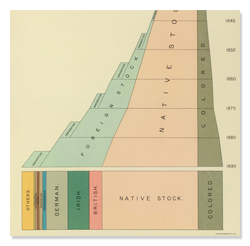

The United States Naturalization Law of 1790 sets the first rules for national citizenship. Naturalization is limited to immigrants who are free white persons of good character, excluding American Indians, indentured servants, slaves, free blacks, and Asians.

The United States also conducts its first census. At that time, there were nearly 4 million non-Native Americans living in the newly established country (Native Americans were not counted in the U.S. Census until 1860). Of those four million people, more than half were English, and 757,000 were of African descent. The next largest groups came from Ireland, Germany, Scotland and the Netherlands, with French, Welsh, Jewish and Swedish people making up the rest of the numbers.

1898 illustration courtesy of Government Printing Office.

Image courtesy of Britannica.com.

1848 The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo is signed between the United States and Mexico, extending U.S. citizenship to Mexican residents of the New Mexico Territory and California.

1849 The California Gold Rush attracts new immigrants from Latin America, China, Australia, and Europe.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia.com.

1850s Anti-Catholic sentiment manifests itself as bigotry against Irish and German immigrants.

Photo courtesty of victoriana.com.

1875 After the Civil War, some states start to pass their own immigration laws, leading to a Supreme Court ruling that immigration was a federal responsibility.

Following a wave of anti-Chinese sentiment building up since the Gold Rush, the first federal immigration law passes. The Page Act of 1875, also known as the Asian Exclusion Act, outlaws the importation of Asian contract laborers, any Asian woman who would engage in prostitution, and all people considered to be convicts in their own countries.

Photo courtesty of chinese-ex-opportunity-race.tumblr.com.

1880s Farming improvements in southern Europe and the Russian Empire created a surplus labor force, while steam-powered ocean liners resulted in lower fares, leading to greater immigrant mobility. Nearly 25 million Europeans from Italy, Greece, Hungary, Poland, and other Slavic countries made up the bulk of this migration, including nearly two million Jews.

Photo courtesty of The Smithsonian Institute.

1882 The Chinese Exclusion Act is passed, limiting the number of immigrants of Chinese descent allowed into the United States for 10 years. The law was renewed in 1892 and 1902.

1892 Ellis Island opens as an immigration station.

1910s The first large-scale migrations from Mexico occur during this time, with over a million Mexican people seeking to escape the Mexican Revolution. The majority of these immigrants are of indigenous descent and from poor and working class backgrounds.

Italian immigration reaches a high, with over two million Italians immigrated in those years. About a third return to Italy, after working an average of five years in the U.S.

In addition, nearly 1.5 million Swedes and Norwegians immigrated to the United States within this period, settling in the Midwest. There were fewer Danish immigrants because of a stronger economy, although, during this time period, many Danish Mormon converts settled in Utah.

Lebanese and Syrian immigrants also arrived in the United States during the beginning of the 20th century. By the 1930s, many of them had moved to the Midwest, where they worked as farmers.

Photo courtesty of Pomona College.

1917 Congress passes the Immigration Act of 1917, which adds a number of “undesirables” banned from entering the country, including, “homosexuals,” “idiots,” “feeble-minded persons,” "criminals," “epileptics,” “insane persons,” alcoholics, “professional beggars,” all persons “mentally or physically defective,” polygamists, and anarchists. It also bars all immigrants over the age of sixteen who are illiterate and creates an "Asiatic Barred Zone," a region that includes much of Asia and the Pacific Islands from which people could not immigrate.

1921 The Emergency Quota Act is passed, restricting immigration into the United States by creating numerical limits on immigration from Europe and the use of a quota system for establishing those limits.

The Emergency Quote Act restricted the number of immigrants admitted from any country annually to 3% of the number of residents from that same country living in the United States as of the U.S. Census of 1890, giving northern European immigrants an advantage over those from eastern Europe, southern Europe, or other, non-European countries. No limits were set on immigration from Latin America.

Photo courtesy of rarenewspapers.com.

1924 Congress passes the Immigration Act of 1924, which reduced the 3% cap set in the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 to 2%. Its primary aim was to restrict immigration of Southern Europeans and Eastern Europeans. It also severely restricted the immigration of Africans and prohibited the immigration of Arabs, East Asians, and Indians. The purpose of the act was "to preserve the ideal of American homogeneity.”

However, immigrants could and did move quite freely from Mexico, the Caribbean, and parts of Central and South America.

Over the next 40 years, the United States began to admit a limited numbers of refugees created by Nazi Germany, Communist rule, a Hungarian uprising, and the Cuban revolution.

Photo courtesy of rarenewspapers.com.

1934 The Tydings-McDuffie Act is passed, which provides for independence of the Philippines and reclassifies all Filipinos as aliens, including those already living in the United States as U.S. nationals. A strict quota is put in place (50 immigrants per year).

Photo courtesy of Briannica.com.

1942 The Bracero Program is created as part of a wartime agreement between Mexico and the United States, allowing Mexican laborers to work in the U.S. under short term contracts in exchange for stricter border. Two million Mexican nationals participated in the program during its existence.

Photo courtesy of University of North Carolina.

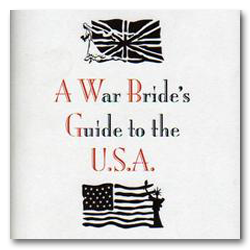

1945 After WWII, the War Brides Act allows foreign-born wives and children of U.S. citizens who have served in the U.S. armed forces to immigrate to the United States.

Photo courtesy of uswarbrides.com.

The 1940s Over a million people immigrated to the U.S. during this time, including 226,000 from Germany, 139,000 from the UK, 171,000 from Canada, 60,000 from Mexico and 57,000 from Italy.

1946 The Luce-Celler Act extends the right to become naturalized citizens to newly freed Filipinos and Asian Indians.

The War Brides Act is extended to include fiancées and fiancés of American war veterans.

Photo courtesy of Wikipedia.com.

1948 The Displaced Persons (DP) Act of 1948 allows over 200,000 Europeans and orphans displaced by World War II to start immigrating.

The War Brides Act expires.

Photo courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park.

| The 1950s In the decade from 1950 to 1960, the U.S. had 2,515,000 new immigrants: 477,000 arriving from Germany, 185,000 from Italy, 52,000 from the Netherlands, 203,000 from the UK, 46,000 from Japan, 300,000 from Mexico, and 377,000 from Canada.

Photo courtesy of neh.gov. |

| 1950 A second Displaced Persons Act allows entry for another 200,000 European refugees to immigrate and required sponsorship of all immigrants.

The Internal Security Act prevents members of fascist or communist groups from entering the country. Photo courtesy of usmm.org. |

| 1952 The McCarran Walter Immigration Act affirms the national-origins quota system of 1924 and limits total annual immigration to one-sixth of one percent of the population of the continental United States in 1920. The act exempts spouses and children of U.S. citizens and people born in the Western Hemisphere from the quota. |

| 1953 The Refugee Relief Act extends refugee status to non-Europeans, with an additional quota of 200,000 granted.

Photo courtesy of Bildarchiv Preusischer Kulturbesitz. |

| 1956 A failed Hungarian revolution results in 245,000 Hungarian refugees.

Photo courtesy of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. |

| 1959 The Cuban revolution drives the upper and middle classes to exile to the United States.

Photo courtesy of Macalester College. |

| 1965 The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 abolishes the National Origins Formula and replaces it with a preference system that focused on immigrants' skills and family relationships with citizens or U.S. residents. A restriction on visas was set at 170,000 per year, with a per-country-of-origin quota, not including immediate relatives of U.S. citizens or "special immigrants" (those born in "independent" nations in the Western Hemisphere, former citizens, ministers, and employees of the U.S. government abroad).

Photo courtesy of New York Daily News. |

1966 The Cuban Adjustment Act is passed, applying to any native or citizen of Cuba who was admitted into the United States after January 1, 1959 and has been physically present for at least one year, making it possible for them to become permanent residents.

Illustration courtesy of Madden via Wikimedia

| 1986 The Immigration Reform and Control Act is signed into law, requiring employers to attest to their employees' immigration status, and making it illegal to hire or recruit illegal immigrants knowingly. It also legalizes certain seasonal agricultural undocumented immigrants, as well as undocumented immigrants who entered the United States before January 1, 1982 and had resided there continuously. An admission of guilt is also required, along with fines and paying back taxes. Candidates must also prove that they are not guilty of crimes and that they possessed minimal knowledge about U.S. history, government, and the English language.

Photo courtesy of dfmpolitics.com. |

| 2013 The Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act of 2013 is introduced to Congress. The bill would make it possible for many undocumented immigrants to gain legal status and, eventually, citizenship. There are also provisions for border security and interior enforcement, as well as reforms to nonimmigrant visa programs. It passed the Senate, but not the House. |

Diversity at Vassar College

Vassar College has a rich history of diversity, beginning with its founding by Matthew Vassar in 1865, who wanted to be able to provide an education to women equal to that of Harvard or Yale. In 1882, Princess Oyama graduated from Vassar, becoming the first Japanese woman to earn a college degree, and, in 1897, Anita Hemmings became Vassar's first black graduate, forty years before the school officially admitted black students.

The 1940s and 1950s brought Vassar's first black staff members, and, in the 1960s multicultural societies and centers sprung up, and Vassar students were majoring in minority studies.

In the late 1980s, the Spanish American Latin Student Association (SALSA ) was founded, becoming Poder Latina/o in 1990, followed by MEChA de Vassar (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán) in 2000. By 2014, the graduating class included nearly 35% students of color, the largest percentage in the college's history, and, in 2015, Vassar College became the inaugural winner of a prize from the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation for excelling in the enrollment and graduation of low-income high achievers.

1865 Matthew Vassar creates Vassar College-a college for women equal to Harvard and Yale.

Photo courtesty of Vassar College.

1882 Princess Oyama (Stematz Yamakawa) graduates, becoming the first Japanese woman to earn a college degree.

Photo courtesty of Vassar College.

1897 Forty years before the college opens its doors to African Americans, Anita Hemmings is Vassar's first black graduate, after passing as a white woman until weeks before graduation.

Photo courtesty of Vassar College.

The 1940s Sterling Allen Brown is hired as Vassar's first black faculty member (part-time).

Photo courtesy of Wikipedia/NFCC#4

1954 Henrietta Smith is hired as its first full-time black faculty member.

1965 Six core faculty members establish the Asian Studies Program.

1967 Students' Afro-American Society (SAS) organizes, holding information seminars about black-oriented issues on campus.

1969 An interdepartmental minor in “Afro-American Studies,” housed at the Urban Center for Black Studies in the city of Poughkeepsie, becomes part of the curriculum. Kendrick House is established as the Afro-American Cultural Center.

Photo courtesy of Vassar College.

1971 Faculty officially approve the creation of an East Asian Studies major.

Photo courtesy of Vassar College.

1976 The Intercultural Center is established in the basement of Lathrop House on campus.

Photo courtesy of Vassar College.

Late 1980s The Spanish American Latin Student Association (SALSA) is founded, becoming Poder Latina/o in 1990.

1990 The Asian Students' Alliance comes into existence as a newly named and updated version of the preexisting Association of Students Interested in Asia (ASIA).

Photo courtesy of Vassar College.

1992 The Korean Students Association is formed.

Photo courtesy of Vassar College.

1994 The Caribbean Students Alliance is formed.

Photo courtesy of Caribbean Students Alliance at Vassar College.

1995 The Southeast Asian Students Alliance is formed.

1998 The Intercultural Center on campus is renamed the ALANA Center, an acronym that includes various communities of color: African American/Black, Latino/a, Asian/Asian-American, and Native American.

Photo courtesy of Vassar College.

2000 MEChA de Vassar (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán) is founded, giving a campus student voice to the Mexican American civil rights movement.

Photo courtesy of Vassar College.

2004 The Department of Chinese & Japanese is founded, focusing not just on language, but also an understanding of literature and culture, integrating arts.

Photo courtesy of Vassar College.

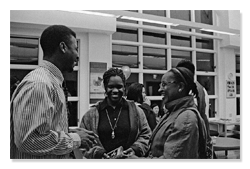

2014 The 2014 graduating class includes nearly 35% students of color, the largest percentage in the college's history.

Photo courtesy of Vassar College.

2015 Vassar College is the inaugural winner of a new no-strings-attached $1 million prize from the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation for excelling in the enrollment and graduation of low-income high achievers.

In the 1980s, Chris Bischof, an avid basketball player, discovered that the best games were to be found at a local league at the Onetta Harris Community Center in East Palo Alto. When he was getting ready to start at Stanford in 1988, he discovered that most of his teammates had no plans to go to college, so, in 1991, he launched a program linking participation in after-school basketball with attendance at a daily study hall.

In 1996, he and Helem Kim established The Eastside College Preparatory School, holding classes at a picnic table in a park. Today, the school boasts a 100% success rate, with all of its graduates going on to college.

1976 Ravenswood High School, East Palo Alto's only high school, closes its doors.

Photo courtesty of Palo Alto Weekly.

1991 Chris Bischof creates the Shoot for the Stars program, which linked participation in after-school basketball with attendance at a daily study hall.

1996 The Eastside College Preparatory School is established by Chris Bischof and Helen Kim in East Palo Alto. Classes are held at a picnic table in a park at first. By the fall, Chris and Helen move their students into Plugged In, a computer learning center. Later, they camped out at a local nonprofit, Families in Transition.

Photo courtesty of Eastside College Preparatory School.

1997 A generous donor offers a 1.6-acre lot at Pulgas Avenue and Myrtle Street, and soon the school grows to 20 ninth and tenth grade students.

1999 Eastside College Preparatory School opens a Middle School.